“In a sort of ghastly simplicity we remove the organ and demand the function. We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.”

(C.S. Lewis)

My last blog post explored the different meanings attributed to love by two of the 19th century’s deepest thinkers. To Friedrich Nietzsche love was a delusion, while to Fyodor Dostoyevski it was the meaning of life. Nietzsche saw in it the urge of the self to possess another, while Dostoyevski viewed it as the giving of oneself to the other. There could hardly be a starker contrast: either love is the will to power in disguise, or it is true self-sacrifice. Their contrasting views on love are rooted in a more fundamental clash between their conceptions of the human person which has transformative implications for the way in which we perceive ourselves and those around us. This post will explore these implications and show how they tie into one of the defining quests of our time: the search for a healthy masculinity.

Beliefs and Behaviours

It seems mysterious how two men as profound as Nietzsche and Dostoyevski, who lived during roughly the same period of time, experienced some remarkably similar twists of fate, and were drawn to similar themes in their work, could nevertheless arrive at such completely opposite views of the world. It is precisely because the clash between their world-views goes all the way down, that it matters so much. Ideas have consequences. They shape how we see the world around us, and the way in which we interact with it. To say that history is full of examples of this would be an understatement. History itself is the example. If a person believes that civilisation is upheld by the whims of a sun god, they will do anything to secure the sun god’s favour. And if staving off the apocalypse happens to involve ritual human sacrifice, they will cheer when the priest rips out the heart of a victim and throws its severed head down the steps of a great pyramid. It would be a mistake to conclude that our modern lives aren’t profoundly shaped by basic beliefs about the world just because we have left behind archaic religion. It is true that a scepticism of grand narratives seems to be characteristic of our age and that city life can seem mundane when compared to the bloody rituals of ancient Mexico. Yet, our behaviour today is no less conditioned by the ways in which we see the world than that of our ancestors. Failing to understand that we can’t not act in accordance with some basic beliefs about the world, makes it impossible to identify which basic beliefs we are acting on at any moment. Modern man may believe that he has outgrown religion, but what really distinguishes him from his ancestors is that he is unaware of how thoroughly his daily life is shaped by quasi-religious beliefs about the nature of the world.

In the modern West, peoples’ basic beliefs seem to have moved towards a kind of materialist individualism. Reality viewed as restricted to the realm of observable objects, and truth as discoverable exclusively by way of the scientific method. For now, we don’t need to explore the implications of the fact that these beliefs are themselves not based on the scientific-method. Instead, let us note that in contrast to scientific truths, which are held to be objective, moral truths are viewed as purely subjective since they cannot be discovered by scientific experiment. Questioning another’s values is always non-sensical and often seen as inherently offensive. After all, since there are no objective truths that could serve as a guide towards common ground, all that disagreement about morality can amount to is the assertion of one’s feelings as superior to those of someone else. Where scientific reality is external and can be discovered, moral values are internal and can only be asserted. While we don’t get to create our own laws of nature, we do get to create our own values. While these beliefs do not tend to promote human sacrifice to the sun-god, they do have far-reaching consequences for how we view ourselves, our relationships and our communities.

Digging Up the Relational Person

To begin sorting out the situation we find ourselves in today we need to look at how the modern view of the “self” contrast with an earlier one. Unearthing this classical view of the human person will inevitably involve a brief (but very rewarding) foray into philosophy. To oversimplify, since the end of the middle-ages the defining dynamic in the West has been what Jacques Barzun called “emancipation”- the progressive liberation of the individual from unchosen bonds. Premised on a view of the human person as naturally abstract from social relationships, this dynamic rejected conceptions of the human person as naturally social. Its authors had pictured the human person as enmeshed in a layered tapestry of social relations starting with the family and reaching up to the (city-) state. Viewing the reconciliation of the person with these various levels of community as essential to the “good life” it described freedom as the ability to choose that which conduced to one’s flourishing as a human person situated in a rich social context. Only as part of communities could humans according to Aristotle live up to their potential. The implications of these basic elements of ancient Greek philosophy became fully evident only much later, when they were brought to completion in light of scholastic thought.

Building on Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas conceived the human person not as abstract, but as profoundly relational. His view of the human person formed part of his wider metaphysics of being as intrinsically relational. What matters for our purposes (you can find a potentially life-changing piece on this here), is that Aquinas saw all existing things as intrinsically active and self-communicative. All existing things are, by virtue of their existence, actively being. Existence is active. In addition, it is self -communicative: by existing, things continuously interact with their environment. They actively “communicate” themselves by giving something of themselves to their surroundings- forming a network of relations with them. For example, falling rain might communicate itself to the grass below it by nourishing it (you can tell that I dropped biology very early). It might communicate itself simultaneously to the laundry someone hang up to dry outside, and to countless other things. An asteroid falling onto the earth will cause a dramatic impact where it lands by communicating some of itself, some of its own properties, to our planet’s surface. Both the drops of rain and the asteroid also communicate themselves to the human mind as phenomena which we can study and understand. While all existing things are actively being themselves and actively self-communicative, only one kind of thing on earth is capable of becoming conscious of its essential relationality, and of willing it. That thing is the human person.

On this view, willing one’s inherent relationality means voluntarily giving oneself. When directed at other persons, this willing act of self-giving becomes love. Paradoxically, it is not by turning inwards, but by moving away from oneself, by giving oneself to the other, that we arrive at ourselves and find what we were meant for. This view of the “relational self” is echoed in Dostoyevski and matches the definition of “Dostoyevski Love” as ‘self-giving’ from my last post. This parallel is not accidental. Both “Dostoyevski Love” and the view of the “self” it is rooted in, embrace relationality and clash with a modern individualist ethos that sees the human person as a kind of free-floating atom whose fulfilment lies in self-assertion rather than in self-giving.

Atomising the Self

Rather than viewing humans as fundamentally relational persons, whose good lies in social flourishing, philosophy began to conceive humans as fundamentally abstract individuals, metaphysically independent from each other as well as from a natural pattern of being. This break set the stage for successive attempts by Western philosophers to justify the thoroughly Christian morality they inherited without reference to a natural order. As Alasdair MacIntyre pointed out, however, these attempts ultimately failed because their authors were unaware of the extent to which they continued relying on quasi-religious beliefs. It was Nietzsche who finally exposed these hidden religious assumptions. In his radical conclusions, he merely recognised the consequences of philosophy’s turn away from the relational person towards the “atomised self” and the parallel abandonment of natural order as a measure for human action.

According to the classical tradition beginning in ancient Greece and culminating in the medieval universities, the path to human flourishing was to conform one’s life to an underlying pattern of reality corresponding with truth and order. Not the simple assertion of your will to get what you feel like you need, but conforming your will to this order, this underlying structure of reality, was taken to be the way to the good life. This idea can be found with striking similarity in Indian, far-eastern and European traditions, which used terms like “Dao” and “Logos” to describe the creative pattern of reality. Where humans conform with the Dao/Logos, participating in it, they were taken to walk the right path and to thrive. If the existence of the Dao/Logos is agreed on, questions about value judgements can be approached with reference to this reality as containing objective value. Where its existence is rejected on the other hand, humans can no more seek their place within a pre-existing cosmic pattern, than they can attempt to orient their judgements by reference to a common objective standard. As Nietzsche concluded, since there is no Dao/Logos to conform one’s will to, one’s will itself becomes primary. The authority of the Dao/Logos over the relational person is usurped by the primacy of the atomised individual’s will. Christianity, according to Nietzsche was a slave-religion designed to prevent the strong from thriving. By holding the most vigorous among us in check, it had stunted humanity and exalted weakness. He believed that the time had come to rid ourselves from its morbid constraints and unleash the vitality of those with the strength to carry out their will.

From Nietzsche to Emotivism

However, Nietzsche’s conclusion was too much for a West that had by then thoroughly internalised Christian habits. One of the main reasons why 20th century Fascism seems so strange and repulsive to us is that it openly glorified strength and power as such, endorsing ruthless violence against the weak. People were prepared to reject the Dao/Logos but did their best to ignore the Nietzschean consequences of this choice. Instead, there emerged a belief that we each get to develop our own moral compasses based on our feelings. As Alasdair Macintyre noted, “Emotivism”, or the grounding of moral standards in one’s (necessarily subjective) emotions, is the ascendant moral framework of our times, even though most Emotivists have probably never heard the term before. If you think that when someone says that supplying arms to Ukraine is right, they really mean that the thought of supplying arms to Ukraine feels good to them, you are an Emotivist. Two seemingly paradoxical consequences follow from this belief: tribal loyalty to one’s in-group, and a deep cynicism about all value judgements.

A basic feature of Emotivism is that it doesn’t allow for constructive discussions about value judgements. There’s no reason to bother trying to understand the other side or to even keep an open mind, if the only basis for your value judgements lies in your own feelings. If value judgements are ultimately based on nothing but brain chemistry, there isn’t anything objective (outside of our brains) to agree about. Of course, you can still try to manipulate someone’s brain chemistry through clever rhetoric or tailored advertisements, but discussing questions of value makes no sense if value is exclusively a product of one’s subjective state of mind. Belief in Emotivism therefore tends to lead people with opposing views to simply shout at each other, refusing to even consider the possibility of common ground. People form tribal groups with others who share their feelings and then try to assert their claims against the political enemy in a kind of war. The label “culture war” is not accidental. The tribal fervour with which culture warriors go at it contrasts sharply with the bloodless cynicism which is the second mark of Emotivism.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

While the culture wars seem to have metastasized from the US, sucking ever more attention into their black hole, the opposing sides have never managed to mobilise more than a fraction of the population. Only a minority of European citizens feels existentially involved in the culture wars. The Emotivists’ cynicism about value judgements on the other hand has achieved a much wider prevalence even among people who have shown no interest in waging toxic online debates. Being cynical about value is only natural if all it can possibly mean is that chemical reactions inside someone’s brain make them feel a certain way about something.

This cynical attitude extends beyond just morality and undermines all kinds of value judgements. It is inconceivable that a building might be beautiful. You’re just feeling warm and fuzzy when looking at it. There is nothing in the Parthenon itself that makes it more appropriate to feel pleased by its sight than by that of a garbage dump. Nothing objective distinguishes their aesthetic value. And just like a piece of art can’t be beautiful, so too historical events can’t be glorious or shameful. Yes, people might release different chemicals when thinking about them, but that’s really all there is to it. It hardly needs to be pointed out that this cynicism breeds contempt of all deep emotion. Someone who fully buys into these beliefs might well read about the Spartans who knowingly sacrificed themselves to block the Persian advance at Thermopylae, and remain unmoved. Reacting to this paradigmatic case of heroism, he might even assume something like the attitude of a scientist observing mice in a laboratory. These men, he might theorise, were really just riled up by hard-wired tribal instincts that drove them to risk their lives for their genetic relatives back in Sparta. According to this reductionist view-point, they, like all of us, were simply motivated by the impulse to protect their genetic offspring. Just like nothing can be good or beautiful, nothing can be heroic, glorious, or worthy of imitation when viewed through the Emotivist lens. The world of Emotivism is one-dimensional. The feeling of awe that overcomes people when confronted with greatness of any kind is smugly reduced to a momentary chemical imbalance and thereby delegitimised as lacking any connection to reality. The consequences of this cynicism in the real lives of people today couldn’t be more vicious.

Reconnecting with Reality

The triumph of the atomised self combined with the rejection of Dao/Logos to create a mutually reinforcing cycle with consequences that could hardly have been foreseen at its inception. Having rejected objective value, we have deprived ourselves of the tools to evaluate and create it. Disoriented, we waste attention and lose touch with reality. Power hierarchies are inevitable, yet we endlessly criticise their existence rather than focussing on how to improve their legitimacy. Surrounded by soulless architecture, we resign ourselves to life in hostile surroundings rather than looking for ways to make our communities beautiful. Confronted with toxic behaviour by men, we deny the reality of the sexes rather than asking what a healthy masculinity ought to look like. Power hierarchies, beauty, and sex-differences are, however, universal facts of life. We can deny, denigrate, or ridicule them all we like. In the end, they will not go away because they are integral parts of the structure of reality. What will happen, however, is that which inevitably happens when reality is rejected. Reality proves you wrong. Ten times out of ten, you lose, reality wins. The truth of this is well illustrated by the debate about masculinity.

My previous post on “Love and Power” ended by emphasising the importance of re-focussing the debate onto the outlines of a healthy masculinity rather than wallowing in the exhaustively repeated bromides about masculinity’s inherent toxicity. I argued that this was necessary, simply because masculinity was real and because real things must be dealt with rather than denied, ridiculed, or denigrated. Failure to do so has already left too many young men without strong role-models to guide them onto the right path. Disoriented and rejected, they are vulnerable to those who affirm an exaggerated and caricaturised form of masculinity. The downstream consequences of our turn away from the relational self and towards the atomised individual striving to assert its will is making itself felt whenever a young man gets drawn in by some internet pick-up artist or worse. Each time a young man starts viewing women as objects to be manipulated for the sake of his own gratification, we see in real life what it means to reject the relational self whose fulfilment lies in self-giving. Prioritising yourself can mean very different things depending on whether you view yourself as essentially disconnected from those closest to you or not. Having explored the context of our current predicament and highlighted some of the key drivers shaping it, we must return to the quest for a healthy masculinity in order to sketch a first draft of its outline. If Dostoyevski-Love, the relational self, and the Dao/Logos have gone badly out of fashion in recent times, it is only by rediscovering them- by rediscovering them as real and true- that we can turn the tide.

Sketching a Healthy Masculinity

If there really is a pattern of reality to which we can either be true or false; if this pattern really calls us to find ourselves by giving ourselves for the sake of others; if the meaning of our lives really lies not in imposing our will through power, but in transformative Dostoyevski Love- the implications are staggering. First of all, it means that we don’t live for our own sake alone. That in itself is a profoundly counter-cultural thing to say in an age of pervasive hedonism. If you truly are at the most basic level relational, tied to the pattern of reality and oriented towards self-sacrificial love, the oft-repeated advice to “just do what you feel like” cannot lead to fulfilment. Rather than living an ego-centred life, we must expand our focus to the real ties that bind us to the world, and in particular to the people, around us. As a matter of fact, these ties exist. An Ubermensch capable of actually thriving as an abstract individual has so far failed to appear. We can’t choose to be independent of these ties because we are human. What we can determine is whether the ties that bind us are shackles holding us back or roots giving us the strength to live up to our potential. If we embrace the relational view of the self, it becomes clear that we can only transform our ties into roots if we begin with an attitude of self-giving first. We don’t exist next to each other and separately from each other, but for each other. Not by denying our ties, but by strengthening them do we thrive. Promising independence, the ego-centred life deprives you of roots and ultimately leaves you shackled to the very things you believed would deliver your freedom. To begin our rough draft of a healthy masculinity, we should start by asking how men in particular can serve those closest to them.

As noted in “Love and Power”, there are certain uncontroversial differences in the psychological make-up of the sexes. Among other tendencies, men have on average higher propensities for physical violence and aggression, lower propensities for both negative and positive emotion and a more pronounced willingness to engage in risk-taking behaviour. These psychological characteristics combine with indisputable physical differences such as higher muscle mass and bone density, that make men on average capable of generating more strength and explosive power. While these differences can be overstated and there is of course significant overlap, they are real and especially pronounced at the extremes. What matters, however, is not so much the mere fact of our differences or how they naturally lead to differential outcomes, but how we view them. Too often is difference presented as somehow deleterious, as a product of indoctrination by a self-serving oppressor class or a bigoted system. There can be no doubt that there are plenty of bigots out there or that all human systems are to some degree corrupt. However, diversity is real and the differences listed above are largely innate. They have been observed across time and space in a variety of cultural contexts. We do ourselves just as great a disservice by denying or denigrating them as when we overstate their importance. Instead of stubbornly trying to eradicate natural diversity, a healthy approach would focus on exploring how different potentials can complement each other in responsible service.

Power and Responsibility

It follows from the relational view of persons as existing for each other, that wherever someone’s position in life gives them power over others, that power must be exercised for the other’s sake. In an inversion of the Nietzschean approach, power means responsibility. Whether this power comes in the form of a corporate leadership position, high political office, or a policeman’s badge- its fulfilment lies in those it is meant to serve. For men as a group, the most obvious responsibility derives from their physiology. The growing impact of digital technology on our lives cannot change the fact that we are physical beings. We rely on our bodies and remain as vulnerable as ever to physical threats. The capacity for greater physical violence therefore comes with a responsibility to master one’s propensity for violence. Not strength in itself is good, but meekness- that is, strength restrained. As GK Chesterton said, it is only the truly strong man who can swing a heavy hammer and bring it to a stand-still just before touching a nail. Unrestrained power is a mark of weakness. True strength (i.e. strength that is true to the Dao/Logos), like any form of true power, lies in service to those who lack that strength and power. Any kind of physical violence directed against vulnerable people is therefore a denial of one’s responsibility as a man. The fact that learning to restrain one’s violence is a key part of a healthy masculinity, does not, of course, mean that there are no situations in which physical violence is not only permitted but called for.

It is in these kinds of circumstances that men’s higher capacity for physical violence and their higher propensity for risk-taking can be employed for worthy ends. As the events since February 2022 have made clear, war is still interested in us Europeans, even if we weren’t all too interested in it for the past thirty years. When one’s home is violently invaded, it must be violently defended if it is to be saved. The Ukrainian people, and especially the soldiers fighting at the front, have stepped up to the task. They have done so not for glory’s or power’s sake, but to defend their country, their cities and their families- in other words, that precious network of relations that defines our lives. And there is glory in that. It is in high-stakes situations like these that the broad-brush labelling of men’s on average higher propensity for risk taking as “toxic” becomes especially harmful. It is precisely that propensity that enables hundreds of thousands of brothers, sons and fathers to leave their families behind and put their lives on the line in the pockmarked fields of Zaporizhia. Again, it is not by denying or denigrating the differences that mark men out as a group, but by orienting them towards their proper ends that we can sketch the outlines of a healthy masculinity. A key pillar of that outline is the orientation of risk-taking and aggression towards service of those that rely on its proper exercise. The institution of Chivalry for example might be seen as an attempt to deal with the fact of male aggression by harnessing it to an ideal of masculinity grounded in service. Where aggression is not ordered towards such service, it becomes Machismo.

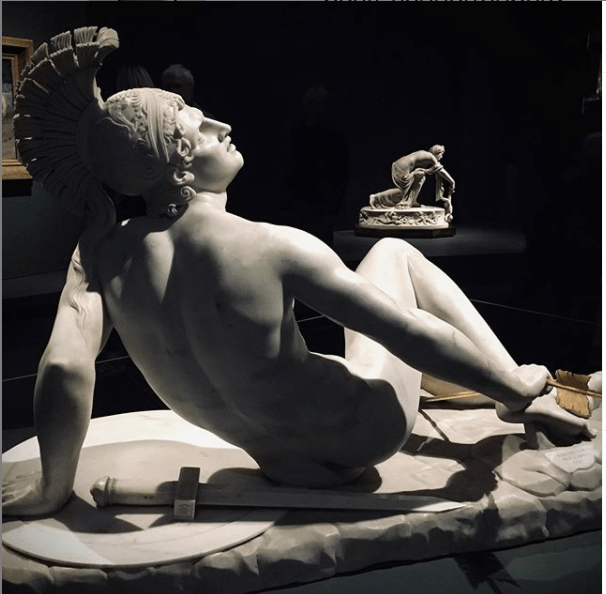

Chest-Day, Best-Day

The example of Ukraine shows the existential significance of answering the questions connected to male aggression and violence. It would, however, be a mistake to think that questions of self-sacrifice are relevant only in wartime. Beyond the battlefield, too, we show our values by what we are prepared to sacrifice for. What do we value most in our lives? Are our actions aligned with our stated values? Are we backing up our words with the sacrifices required? While it is important to meditate on and find answers to these all-important questions, it is not enough to just think about them. We aren’t computers that can simply execute a given task. We need ideals to inspire us, and courage to keep us going when the odds are not in our favour. In his essay “Men without Chests”, CS Lewis pointed out that the ubiquitous cynicism about emotions made it difficult for young people to build up the emotional strength required to persevere in the face of daunting challenges. Yet, all the greatest things in life require this kind of perseverance. We wonder why young men don’t show more self-sacrifice but make fun of the very concept. We reduce all emotion to mere brain chemistry and wonder why our Europe is the continent in which the fewest young people would be prepared to defend their homes in a war. We demand that men step up but turn masculinity into a joke.

CS Lewis recalled the ancient Greek idea that “the head (reason) rules the belly (emotion) through the chest”, where “emotions (are) organised by trained habit”. CS Lewis noted that contemporary society had completely forgotten about the need for such trained habit because it looked down on all deep emotion. It had, in other words, produced men without chests. Since Lewis wrote his essay our predicament has not improved. To the contrary, both Machismo and the denial of masculinity are on the rise. Grounded in a recognition of humans as existing for each other, a healthy masculinity is one that embraces responsibility. It requires that power be used for the sake of the powerless and in defence of those goods that make life valuable. We should foster the development of the trained habits healthy masculinity relies on and start by recognising that there is a rightful place for deep emotion where it is true to the Dao/Logos. Building these habits will take time, but like the development of one’s physical chest in the gym, it is well worth it. Taking this rough draft of a healthy masculinity as a starting point, a re-focused debate would be a first step for our societies to once again produce men with chests.